Cold is the Catastrophe

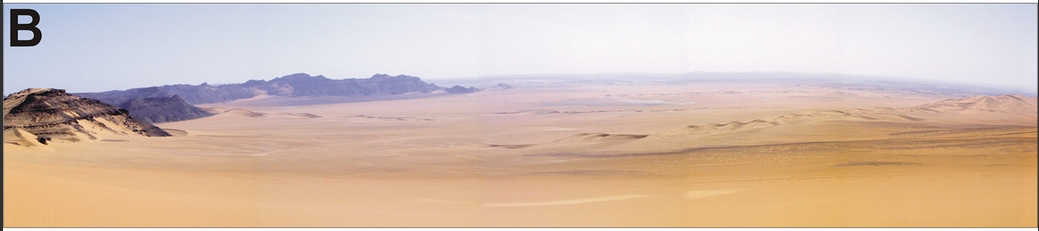

A hotter world might not be so horrible. Back in the early Holocene, 10,000 years ago, rivers flowed in the middle of the Sahara desert, and they were filled with fish. The photo above is what remains of Takarkori Lake today. If only climate change could bring back the fish?

While we were distracted in 2020, researchers published a paper about an trove of bones and body parts they had dug out of a cave in Southwest Libya, which is roughly the middle of the Sahara today. Surprisingly they found 17,551 bones, and even more surprisingly, 80% of them were from fish.

The people who dined there were catching tilapia and clariid catfish, and sometimes the odd mud turtle, mollusc and a crocodile or two. The lake (pictured above) is about 6 kilometers from the cave (below), and all the bones appear to be human refuse. It’s kind of the ultimate archaeological FOGO dump.

Somehow, this restaurant that stayed open for 6,000 years left behind layer after layer of undisturbed dining history. Gradually, over thousands of years the diners ate less fish, and more beef, goat and mutton.

Amazingly, 17,000 bits of bone and bits were found in an area of just 150 meters square. Somehow, against the odds, the researchers were able to identify every single fish bone. It seems astonishing, except the odds were 50:50 that each bone was either a Tilapia or a Clariid catfish. The residents may have been a bit tired of eating the same two fish.

While the rivers and wetlands may have had a lot of fish, there wasn’t much variety.

The authors, Wim van Neer et al, speculate that the fish probably spread to these lakes via massive flooding events that washed them over the land. (Imagine how big those floods would have to be?) They wonder if the odd bird might have dropped some fish eggs, but don’t think it is as likely. Apparently sometimes even storms can pick up fish and fling them far away. If humans ever did control the climate and fix it in its current state, they would stop life returning to the desert and call it a “win” for the environment. Crazy eh?

During this hot Holocene era, there were many other rivers across the Sahara that don’t flow there today. The lakes near Takarkori dried up during the sudden shocking cold snap 8,200 years ago, but came back after a few centuries. (Just more climate change!) Sometime around 5,500 years ago they dried up for good (or bad, if you were a nomadic herder).

One river nearby managed to keep flowing until Roman times, about 2,000 years ago.

Map of Saharan rivers and water systems of the Holocene. Fig 14. Extant occurrence of selected aquatic species (fish, crocodile, and turtle) in North Africa waterways.

Crocodylus distribution has to be considered continuous in the present waterways south of the Sahara desert and along the Nile River south of Aswan.

The remnants at the cave cover an era 6,000 years long

It is somewhat sobering to be reminded of just how many generations have come and gone, and how different their lives must have been. What would they think if they saw the barren desert now?

The first humans to live in the cave arrived about 10,000 years ago. Permanent settlements appeared around 8,300 years ago with dairy cattle arriving 800 years later. By 6,000 years ago the site was used for brief visits by herders of goats and sheep during the winter.

From the paper:

The first inhabitants at Takarkori rock shelter were early Holocene hunter-gatherer-fishers locally called “Late Acacus” (LA1-3: ca. 10,200–8000 cal BP). Archaeological and archaeobotanical evidence indicates prolonged, albeit seasonal, residential occupation and a delayed-return system of resource exploitation [13, 33, 34, 35].

Stone structures of different size and functions (huts, windbreaks, platforms, etc.) and large fireplaces, together with large grinding stones and abundant pottery also point to semi-sedentary lifestyle, as indicated by other coeval sites in the region, such as Ti-n-Torha East, Uan Afuda and Uan Tabu [7, 36, 37]. The earliest evidence of Pastoral Neolithic herders (EP1-2) dates to ca. 8300 cal BP, mostly represented by the burial of women and children [38].

A full pastoral economy based on cattle exploitation including dairying is attested from approximately 7100 years cal BP [39], when the shelter is occupied seasonally (MP1-2), likely from the end of the rainy season and during the dry winter [13, 40]).

Nomadic herders (LP1, ca. 5900–4650 years cal BP), mostly focussing on small livestock (sheep/goat) rather than cattle, briefly camped at Takarkori during the winter, using much part of the area for penning the animals, with a thick, hardened layer of ovicaprine dung closing the sequence

The current Sahara desert

Just to remind us of how incredibly vast it is:

The press release:

Fish in the Sahara? Yes, in the early Holocene

ScienceDaily, February 2020

Catfish and tilapia make up many of the animal remains uncovered in the Saharan environment of the Takarkori rock shelter in southwestern Libya, according to a study published February 19, 2020 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Wim Van Neer from the the Natural History Museum in Belgium, Belgium and Savino di Lernia, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, and colleagues.

Today, the Saharan Tadrart Acacus mountains are windy, hot, and hyperarid; however, the fossil record shows that for much of the early and middle Holocene (10,200 to 4650 years BP), this region was humid and rich in water as well as life, with evidence of multiple human settlements and diverse fauna.

Rock shelters within the Tadrart Acacus preserve not only significant floral and faunal remains, but also significant cultural artifacts and rock art due to early Holocene occupation of these shelters. In this study, the authors worked with the Libyan Department of Antiquities in excavating parts of the Takarkori rock shelter to identify and date animal remains found at this site and investigate shifts in the abundance and type of these animal remains over time.

Fish remains made up almost 80 percent of the entire find overall, which numbered 17,551 faunal remains total (19 percent of these were mammal remains, with bird, reptile, mollusc, and amphibian remains the last 1.3 percent). All of the fish and most of the other remains were determined to be human food refuse, due to cut marks and traces of burning — the two fish genera at Takarkori were identified as catfish and tilapia.

Based on the relative dates for these remains, the amount of fish decreased over time (from 90 percent of all remains 10,200-8000 years BP versus only 40 percent of all remains 5900-4650 years BP) as the number of mammal remains increased, suggesting the inhabitants of Takarkori gradually focused more on hunting/livestock. The authors also found the proportion of tilapia specifically decreased more significantly over time, which may have been because catfish have accessory breathing organs allowing them to breathe air and survive in shallow, high-temperature waters — further evidence that this now-desert environment became less favorable to fish as the aridity increased.

The authors add: “This study reveals the ancient hydrographic network of the Sahara and its interconnection with the Nile, providing crucial information on the dramatic climate changes that led to the formation of the largest hot desert in the world. Takarkori rock shelter has once again proved to be a real treasure for African archaeology and beyond: a fundamental place to reconstruct the complex dynamics between ancient human groups and their environment in a changing climate.

REFERENCE

“Wim Van Neer, Francesca Alhaique, Wim Wouters, Katrien Dierickx, Monica Gala, Quentin Goffette, Guido S. Mariani, Andrea Zerboni, Savino di Lernia. Aquatic fauna from the Takarkori rock shelter reveals the Holocene central Saharan climate and palaeohydrography. PLOS ONE, 2020; 15 (2): e0228588 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228588