Peer Review has been a sixty year experiment with no control group

It’s touted as the “gold standard” of science, yet the evidence shows Peer Review is an abject failure.

It’s touted as the “gold standard” of science, yet the evidence shows Peer Review is an abject failure.

There are 30,000 scientific journals that publish nearly 5 million articles a year, and the only thing we know for sure is that two-thirds of papers with major flaws will still get published, fraud is almost never discovered, and peer review has effectively crushed groundbreaking new discoveries.

By Adam Mastroianni, Experimental History

The rise and fall of Peer Review

Why the greatest scientific experiment in history failed, and why that’s a great thing

For the last 60 years or so, science has been running an experiment on itself. The experimental design wasn’t great; there was no randomization and no control group. Nobody was in charge, exactly, and nobody was really taking consistent measurements. And yet it was the most massive experiment ever run, and it included every scientist on Earth.

It seemed like a good idea at the time, instead it was just rubber stamp to keep the bureaucrats safe. As government funded research took over the world of science after World War II, clueless public servants wanted expert reviewers to make sure they weren’t wasting money on something embarrassingly stupid, or fraudulent. They weren’t search for the truth, just protecting their own necks.

Scientifically, there’s no evidence supporting peer review:

Here’s a simple question: does peer review actually do the thing it’s supposed to do? Does it catch bad research and prevent it from being published?

It doesn’t. Scientists have run studies where they deliberately add errors to papers, send them out to reviewers, and simply count how many errors the reviewers catch. Reviewers are pretty awful at this. In this study reviewers caught 30% of the major flaws, in this study they caught 25%, and in this study they caught 29%. These were critical issues, like “the paper claims to be a randomized controlled trial but it isn’t” and “when you look at the graphs, it’s pretty clear there’s no effect” and “the authors draw conclusions that are totally unsupported by the data.” Reviewers mostly didn’t notice.

In fact, we’ve got knock-down, real-world data that peer review doesn’t work: fraudulent papers get published all the time. If reviewers were doing their job, we’d hear lots of stories like “Professor Cornelius von Fraud was fired today after trying to submit a fake paper to a scientific journal.” But we never hear stories like that. Instead, pretty much every story about fraud begins with the paper passing review and being published. Only later does some good Samaritan—often someone in the author’s own lab!—notice something weird and decide to investigate. That’s what happened with this this paper about dishonesty that clearly has fake data (ironic), these guys who have published dozens or even hundreds of fraudulent papers, and this debacle:

Gotta love this graph!

Wait a second, these are not real error bars … the author literally just put the letter “T” above the bar graphs 😭 pic.twitter.com/KKtTGRHFaw

— Josemari Feliciano (@SeriFeliciano) November 28, 2022

That graph was published, in Advances in Materials Science and Engineering. After peer review failed, but “Twitter Review” succeeded in discovering the error bars were deliberate typos, so-to-speak, it has been retracted. But how much other junk got set in print in 4.7 million articles a year?

Why don’t reviewers catch basic errors and blatant fraud? One reason is that they almost never look at the data behind the papers they review, which is exactly where the errors and fraud are most likely to be. In fact, most journals don’t require you to make your data public at all. You’re supposed to provide them “on request,” but most people don’t. That’s how we’ve ended up in sitcom-esque situations like ~20% of genetics papers having totally useless data because Excel autocorrected the names of genes into months and years.

Mastroianni makes the case that the whole point of peer-review was to deal with the explosion of new government funded papers. Once the bureaucrats took command of science the main aim was not “brilliant discoveries” but just not to fail embarrassingly. Thus peer review was merely a bureaucratic safety value that cost no dollars but gave a rubber stamp to “government science”. It became the committee cover that “protected” jobs — but in a sense all of science became a bureaucratic protectorate:

Why did peer review seem so reasonable in the first place?

I think we had the wrong model of how science works. We treated science like it’s a weak-link problem where progress depends on the quality of our worst work. If you believe in weak-link science, you think it’s very important to stamp out untrue ideas—ideally, prevent them from being published in the first place. You don’t mind if you whack a few good ideas in the process, because it’s so important to bury the bad stuff.

But science is a strong-link problem: progress depends on the quality of our best work. Better ideas don’t always triumph immediately, but they do triumph eventually, because they’re more useful. You can’t land on the moon using Aristotle’s physics, you can’t turn mud into frogs using spontaneous generation, and you can’t build bombs out of phlogiston. Newton’s laws of physics stuck around; his recipe for the Philosopher’s Stone didn’t. We didn’t need a scientific establishment to smother the wrong ideas. We needed it to let new ideas challenge old ones, and time did the rest.

Weak-link thinking makes scientific censorship seem reasonable, but all censorship does is make old ideas harder to defeat.

Mastroianni argues that having a meaningless rubber stamp is worse than no rubber stamp at all — as if the FDA inspected meat just with a sniff, and then put on sticker saying “Inspected by the FDA”. It’s dangerous…

If you want to sell a bottle of vitamin C pills in America, you have to include a disclaimer that says none of the claims on the bottle have been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Maybe journals should stamp a similar statement on every paper: “NOBODY HAS REALLY CHECKED WHETHER THIS PAPER IS TRUE OR NOT. IT MIGHT BE MADE UP, FOR ALL WE KNOW.” That would at least give people the appropriate level of confidence.

“Hooray We Failed” he says. No one was in charge of this experiment, so no has the job of saying it’s over. Mastroinni appoints himself, and declares it “done”.

What should we do now? Well, last month I published a paper, by which I mean I uploaded a PDF to the internet. I wrote it in normal language so anyone could understand it.

Then thousands of people read it, retweeted it and he got more reviews and feedback than he’s ever had. NPR asked him for an interview, and professors offered him ideas. The free market in ideas will always beat the bureaucratic committees. Blog science, substack articles and tweets may yet rescue science from the government funded strangehold. The only formula for finding the truth is free speech.

In his followup article he talks about the response to his article: the fears and the inevitable rage and yelling from the people who’ve worked so hard at climbing the ladder of citations.

Richard Smith, the former editor of the British Medical Journal, commented:

It’s fascinating to me that a process at the heart of science is faith not evidence based. Indeed, believing in peer review is less scientific than believing in God because we have lots of evidence that peer review doesn’t work, whereas we lack evidence that God doesn’t exist.

It’s a long feature article and well worth reading. Though it’s no accident, of course, that archaic bad systems of publication still control science 30 years after the spread of the internet — the gatekeepers of science and government don’t want to lose control of the monoculture they created.

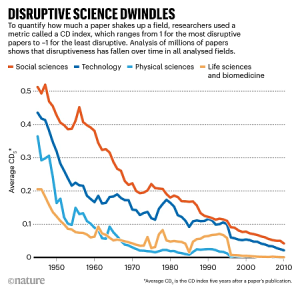

See also — Everywhere in science there’s a mysterious lack of ground-breaking papers

h/t Bill in AZ, via Vox Populi