Dennis Avery reminds us of just how painfully cold the Little Ice Age was (see below) and also pointed me to this excellent historical description:

The Great Irish Frost of 1740, Longest Period of Extreme Cold in Modern European History

Biot Report #442:July 13, 2007

An extraordinary climatic shock—the Great Frost—struck Ireland and the rest of Europe between December 1739 and September 1741, after a decade of relatively mild winters. Its cause remains unknown. Charting its course sharply illuminates the connectivity between climate change and famine, epidemic disease, economies, energy sources, and politics. David Dickson, author of Arctic Ireland (1997) provides keen insights into each of these areas, which may have application to human behaviors during similar future climatic shocks. The crisis of 1740-1741 should not be confused with the equally devastating Great Potato Famine in Ireland of the 1840s.

Though no barometric or temperature readings for Ireland (population in 1740 of 2.4 million people) survive from the Great Frost, Englishmen were using the mercury thermometer invented 25 years earlier by the Dutch pioneer Fahrenheit. (1) Indoor values during January 1740 were as low as 10 degrees Fahrenheit. The one outdoor reading that has survived was 32 degrees Fahrenheit, not including the wind chill factor, which was severe. This kind of weather was “quite outside British or Irish experience,” notes Dickson. (1)

How different life would have been then. We are reminded just how useful it is to stay one step ahead of mother nature, if we can.

Climax of Catastrophe

The catastrophe climaxed in spring-summer 1741. Dysentery and typhus raged through county after county. One observer wrote:

“Mortality is now no longer heeded; the instances are so frequent. And burying the dead, which used to be one of the most religious acts among the Irish, is now become a burthen: so that I am daily forced to make those who remain carry dead bodies to the churchyards, which would otherwise rot in the open air; otherwise I assure you the common practice is to let the tree where it fall, and if some good natured body covers it with the next ditch, it is the most to be expected. In short, by all I can learn, the dreadfullest civil war, or most raging plague never destroyed so many as this season. The distempers and famine increase so that it is no vain fear that there will not be hands to save the harvest.” (14)

More riots occurred as wealthy person increasingly feared that by the summer of 1741, the epidemics would reach them. This fear led to a purge of diseased Dublin vagrants who officials led to the Workhouse where they died in great numbers. In the year beginning June 1741, for example, more children died in the Workhouse (700 children) than were actually admitted into it, according to Dickson.

MAUNDER MINIMUM 1740—REPLAY IN 2020?,

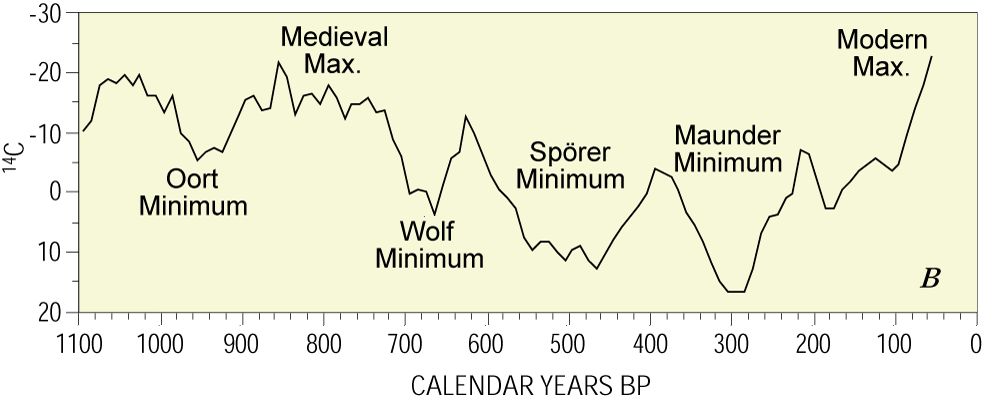

Carbon-14 record for last 1,100 years (inverted scale). Solar activity events labeled. Source: http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs-0095-00/

A reader recently pointed out a fascinating temperature comparison—between 1700 AD and today. He marked two sections of the world’s oldest temperature record–Central England Yearly Average Temperature 1660–2008: The first section showed our famous recent temperature surge from 1976–1998. He also marked a similar strong temperature surge from AD 1688–1738.

The killer in the comparison is that the temperature surge after 1688 was followed by a sudden plunge into one of the coldest periods in the entire Little Ice Age. The cold of 1739-40 was called The Great Frost, and it devastated Europe from Italy to Iceland.

The linkage? The Great Frost followed a period of very few sunspots—The Maunder Minimum (1645–1715). Today, we know that fewer sunspots predict colder temperatures, and the modern world has just undergone a similar dearth of sunspots, from 2007 to 2011.

During the Maunder period, Europe’s glaciers were much larger than today; it was the Little Ice Age, after all. But the glaciers didn’t advance during the sunspot dearth. The winters of the 1730s were actually fairly warm. But during and after the winter of 1739, glaciers advanced strongly through France and Germany, and north into Sweden, Norway and Iceland and didn’t retreat for the next 50 years.

Ireland suffered the most severely. In the depths of the winter of 1739-40, winds and terrible cold intensified. Rivers, lakes, and waterfalls froze and fish died in the first few weeks of the Great Frost. Coal dealers found their coal piles and unloading docks frozen solid. Mill-wheels froze, so the millers and bakers could produce no bread.

Ireland’s crucial potato crop—normally left in the ground until needed for food—froze underground. The tubers were ruined for food, and useless as seed for the following year. The following spring came drought, and the winds remained fierce. The winter wheat and barley sown the previous fall died in the fields. Sheep and cattle died in the pastures. The fall of 1740 saw a small harvest, but the dairy cattle had been so starved that few of them bore calves. Milk production plummeted as the cows’ milk dried up.

That winter, blizzards ranged along the coast, and great chunks of ice sweeping down the River Liffey sank vessels in the harbor. Dublin wheat prices rose to all-time highs.

Meanwhile dysentery, smallpox, and typhus were ravaging a weakened population. Farm workers had seldom gone to town when they had food on their tables; now they wandered in seeking food or relief assistance—and died in great numbers.

The climate disaster finally ended in the summer of 1741. An estimated 400,000 people had died. Desperation gripped the people following both the Great Frost and a warmer bad-weather famine from 1726 to 1730. The harsh variability of the Little Ice Age was being felt full force. Thousands of Irish families began immigrating to America. The emigration of Ulster Presbyterians, for example, peaked between 1740 and 1760. Ministers took whole congregations to the Carolinas and Virginia, where they found like-minded people and cheap farmland.

Usually, there’s about a ten-year lag between sunspot changes and their impact on earth’s temperatures. The sunspots began predicting lower temperatures about 2000, for instance, and the cooling trend began eight years later in 2007. Now the sunspot minimum that just ended is predicting quite serious cold, perhaps about 2020.

Don’t throw away your electric blankets—and make sure that greenhouse emissions limits don’t steal the electricity to heat them.

H/t Bob S and thanks to Dennis for permission to reprint his work.