Fires this week in South West WA have caused two deaths, burned 72,000 hectares and destroyed 143 homes, wiping out 80% Yarloop. But it’s all happened before, and the fires were bigger, worse, and burned a larger area. The ABC have described the infamous fires of 1961 before, but there doesn’t seem to be any mention of the history of these historic fires in their current news. Surely it’s relevant? No one at the $1 billion dollar agency did the internet search that an unfunded blogger did.

In January 1961 the remnants of cyclones meant dry thunderstorms lit fires in the hot dry South West of Western Australia. Ten separate fires began in the same area near Dwellingup. They wiped 60 year old small timber towns off the map, and razed 123 houses. Over the next 41 days, fires continued to burn, destroying 160 buildings and burning through hundreds of thousands of hectares of land (134,000 hectares in the Dwellingup Fire, but 1.5 million hectares burned in SW WA that summer -PDF ). The damage bill would come to $35 million. Somehow, incredibly, no lives were lost.

The fires of 1961 in South West Western Australia:

“Temperatures soared to 41C and winds of 60km/hr whipped” the South West.

“Dwellingup sustained considerable damage and had to be virtually rebuilt.

Not so lucky were the small mill communities of Holyoake, Nanga Brook, Marrinup and Banksiadale which were literally wiped off the map. In fact, following the fires, a decision was made not to rebuild these towns.”

South West WA is one of the most fire prone regions of the world, says Bushfire CRC:

South-west Western Australia is one of the most fire-prone regions in the world due to the combination of a Mediterranean-type climate with hot dry summers and the presence of large areas of flammable native vegetation. It is also a biodiversity hotspot where the role of fire is key. Prescribed fire has been used extensively in forest landscapes since the 1960s to mitigate the impacts of bushfires on the community and on environmental values including biodiversity. The ecological implications of prescribed burning, however, remain contentious.

The response to the 1961 devastation was to have a Royal Commission, get radio equipment, and do better prescribed burning.

Prescribed burning in WA became a serious ongoing practice after these shocking 1961 fires and continued until the mid 1990s, but has been reduced in the last two decades. (See below for details).

A group called Bush Fire Front (BFF) describe problems with forest management in WA, pointing out that there were not many major problems from 1962 – 1985 because WA had such an active fire management plan. It was tested when Cyclone Alby swept through WA in April 1978 with winds of up to 130km hour, the lightning igniting as many as 65 wildfires. Despite this extreme situation, the total damage was much lower than either 1961 or 2016 fires because the area was so well prepared with reduced fuel loads. The BFF page (below) may be a few years out of date, I suspect burning off has increased in the last few years, but this is the kind of discussion and the numbers we should be discussing. Where are the investigative journalists at the ABC or the West Australian?

DEC fire management on its forested land in the South West is inadequate because:

- Fuel reduction burning cycles are too long

- The annual burning target is too low.

- DEC has an annual target of 200,000 ha for a forest estate of about 2,500,000 ha, which gives an average burning cycle of 12 years. Despite that overall figure there are significant areas of forest carrying fuels older than 20 years. BFF believes that the negligible wildfire losses of the 1961-1985 period, where the average area burnt each year was about 300,000 ha, indicates that a figure closer to that area is necessary to provide adequate protection against major wildfires.

- DEC has an annual target of 200,000 ha for a forest estate of about 2,500,000 ha, which gives an average burning cycle of 12 years. Despite that overall figure there are significant areas of forest carrying fuels older than 20 years. BFF believes that the negligible wildfire losses of the 1961-1985 period, where the average area burnt each year was about 300,000 ha, indicates that a figure closer to that area is necessary to provide adequate protection against major wildfires.

- They cannot reach their annual target anyway

- From 2000 to 2008, the average area of burning each year by DEC was 149,000 ha This means that in the period 2000-2008 alone, the backlog of burning was over 400,000 ha. This backlog will never be made up, so the outlook is for steadily increasing fuel loads in our forests, therefore steadily increasing fire hazards.

- Their burn planning processes are too complex

- Implementation of burns is ineffective

- Smoke minimisation procedures severely limit the amount of burning close to the Metropolitan area

- Reserves managed by DEC such as the regional parks, receive very little active fire management.

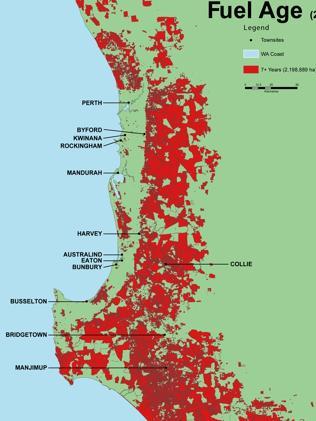

In January 2014, Peter Law, The Sunday Times (news.com), warned that there was too much unburned forest in WA with a high “fuel age”. Small controlled cool burning fires are easy to manage in forest that has been recently burned, but once the forest has seven years of fuel buildup, even controlled burns become risky.

Areas of SW WA which had not been subject to prescribed burning in the last seven years, as of July 2013

The map reveals the build-up of fuel – combustible trees, shrub and ground litter – aged over seven years near Perth and in the South-West.

As of last July, there was almost 2.1 million hectares of fuel aged seven years and older across WA, the paper reveals. Fuel aged under six years spanned 944,000ha.

Bushfire Front chairman Roger Underwood described the accumulation of older fuel – about eight tonnes per hectare – near poorly prepared residential areas as WA’s “ticking time bomb”.

“This map demonstrates that 80% of South-West forests and national parks are now in a situation where firefighters will not be able to tackle or surpress a fire even in moderate conditions because of the very heavy fuels,” Mr Underwood said.

In 2012/13, DPaW achieved just 23,648ha of its annual prescribed burn target of 200,000ha in the South-West.

This is the age it becomes almost impossible to control on even average summer conditions – let alone catastrophic days with soaring temperatures and fast winds.

“DPaW said its prescribed burning program is governed by a number of factors, including weather conditions.

“However, over the past 20 years, the department has met 79 per cent of its cumulative annual target,” a spokeswoman said.”

Current government fire management just does not understand the reasons that fires get “beyond control”. Here’s the current Dept of Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner saying that nothing could have stopped this damage. There is no mention of fuel loads:

DFES Commissioner Wayne Gregson…

“Over the past four or five days we have been at full-on war with mother nature, I’m told we have not seen a firestorm of this magnitude, in terms of the size,” he told 6PR radio on Monday.

Mr Gregson said residents were told not to stay to defend their properties without a plan and to not rely on the local water and electricity supply, adding the blaze could not be defended with a garden hose.

“I sometimes think people don’t recognise the enormity of the fire front,” he said.

“I don’t believe anything could have stopped that fire impacting Yarloop.

“Fires get to a point where they just cannot be defended, either from a frontal attack or by the air.”

Yes, they get too big to defend when we haven’t done the burning off to reduce fuel loads. The fire boss is being criticized for all kinds of things, but the real problem that we ought to be trying to prevent the uncontrollable fires in the first place.

We keep learning the same lessons

Nearly 70 years ago, even the Women’s Weekly understood we needed to clear the underbrush. The December 1957 issue warned that Australia’s worst enemies are fire and flood, and people keep forgetting to prepare for them.

DONT LET IT HAPPEN AGAIN

FOR Australia’s total history of nearly 170 years, two of her worst enemies have been fire and flood. But after seven generations, Australians still won’t learn that although these two killers and destroyers can’t be prevented they can be minimised and controlled.

Australians are casual folk with short memories. They live thousands of miles apart. A bushfire in the Blue Mountains of N.S.W. or in South Australia means nothing at the time in North Queensland or Western Australia.

Because fire and flood are seldom more than localised, there is never a sense of national urgency, of the need to organise and tackle a problem in a big way.

The flood waters recede . . . the fires go out. . . homes are rebuilt . .. tragedies become memories . . .

Until the next time, which to most Australians is remote, far off. But next times do happen. Disasters that could have been prevented recur. And little or nothing has been done in between to save those lives lost or to prevent that valuable timber country from being ruined.

Every spring fire-hardened experts warn that it can and will happen again. And every summer some area gets burnt out because local authorities and citizens in that area have not taken the trouble to clear dry underbrush. After every summer when the fires are out Australians forget – until the next time.

Here are some of the details of the improvements in fire management after the 1961 fires:

The upshot, for forest fire management, was confirmation that the fuel reduction burning approach was necessary and appropriate, but needed to be placed on a more scientific footing, and needed to be expanded. The response of the Forests Department was to commence a comprehensive fire behaviour research program and to investigate new techniques for fuel reduction burning, aimed at increasing productivity of existing resources. This research program was, and remains, unique in Australia. Only in CSIRO has there been any similar fire research program. In addition, improvements were made in equipment, radio communications and weather forecasting. Aerial fire detection became an essential pat of the fire detection system.

The fuel reduction burning program became progressively better planned, taking into account a wide variety of factors, including community protection, matching burn specifications to forest management objectives, protection of rare fauna and flora, visual amenity along tourist routes and smoke management. A burn monitoring and evaluation system was introduced. The technique of fuel ignition was greatly improved, thanks to fire behaviour research and culminated in the development of aerial ignition procedures. Using aerial ignition, the Department was able to achieve significant gains in productivity, to the point where it became possible to carry out individual burns as large as 20,000 ha in a single day. A burn of this size was, however, unusual. Most aerial burns were of the order of 5,000 ha.

The worst fires in Australia’s history happened when CO2 levels were ideal. Read about the apocalyptic Black Thursday in 1851 in Victoria.

We wrote about the importance of fuel loads in 2013:

People have been burning off to keep fuel loads low in Australia for thousands of years.

Current fuel loads are now typically 30 tonnes per hectare in the forests of southeast Australia, compared to maybe 8 tonnes per hectare in the recent and ancient pasts. So fires burn hotter and longer. (The figures are hard to obtain, which is scandalous considering their central importance.)

Bill Gammage wrote an excellent book, The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia, which was awarded the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History and the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award in 2012. The first Europeans in Australia noted over and over that Australia looked like a country estate in England, like a park with open woodlands, extensive grassy patches, and abundant wildlife. Where Europeans prevented aborigines from tending their land it became overgrown, and the inevitable fires became dangerous and uncontrollable.

Particularly memorable is the account of driving a horse and carriage from Hobart to Launceston in the early 1800’s, before there were any roads, simply by driving along the grassy park underneath the tree canopies. Try doing that today.